Thirty Years of "Smart Growth" in Oregon

This paper attempts to condense all the literature that has been written about Oregon's unique program of land-use planning, which came out of the environmentalist movement in the early 1970s. The best-known feature of this system is the "urban growth boundary," which is a line around each city in the state that clearly marks what land is city and country. Most of the writing about this stuff is deadly, deadly boring, and my paper is unfortunately a reflection of that material. I think this is still interesting, though, because historians often write about how things got fucked up in the past, about chances missed and alternatives not taken. Oregon is a case where a constructive solution might actually have been pursued, and that in itself is a nice change of pace.

...

"For nearly three decades, Oregonians have built and nurtured a system and philosophy of land-use planning that is the envy of people throughout the world." Although rather strongly put, the sentiment behind these words can be found in almost any newspaper, magazine or history book that discusses planning in Oregon. Designers, politicians, activists and pundits have a penchant for words like "benchmark" or "model" when discussing the state, and planners elsewhere have looked with envy to a land where thoughtful organization of space is both embraced and enforced. The above statement, written by a longtime planner in response to a rare attack on the achievements of Oregon's leading city, bears all the marks of a classic Portland plaudit: the author put the emphasis on people rather than the state ("Oregonians") and implied that the system itself possesses some kind of unique philosophy or culture that makes its success possible. This sense of possessiveness, of involvement in the process of planning, appears throughout works on Oregon land-use policy, alongside some substantial minimum of respect for the program's accomplishments.

Doubts, however, have not been unknown. As early as 1974, when the program was in its infancy, Charles E. Little reflected on the legislative process that brought comprehensive, statewide planning into existence and wondered if too many compromises had been made: "The question now is, for Oregonians as well as students of their land-use legislation, did anything worthwhile really happen?" Thirty years have passed and the answer to that question is not abundantly clear. The compromises appear not to have been mere expedients of state politics and legislative committees but, rather, an integral part of the system itself. The available scholarship suggests that, since its inception, Oregon's unique land-use program has survived by accomodating threats and turning political challengers into stakeholders of the planning regime. Unsurprisingly, developers have figured prominently in debates and studies about planning, since the decisions of state and local governments can directly determine how (and whether) land is used. The powerful role of homebuilders and their ilk, as both friends and enemies, has led scholars to question whether planning was ever anything but a tool of business, but most research suggests a more complex picture. The Oregon land-use program has been able to go far by reaching far, incorporating numerous interests into its constituency and offering something to almost everybody. Planning has, so far, reconciled contradictions to the sufficient satisfaction of the interested groups, although it may have created new contradictions in the process, laid away for future discovery.

The first work on the subject, Little's The New Oregon Trail charted the tortuous legislative process that eventually created the state-local partnership and "urban growth boundary" system that have defined Oregon planning ever since. Little followed the efforts of state Senator Hector Macpherson, a dairy farmer who began to push for comprehensive planning out of fear that farmland would be gobbled up in the rapidly urbanizing Willamette Valley. Most of the state's significant cities were located in this region between the Coastal and Cascade mountain ranges, but the Valley also included the most fertile farmland in Oregon. Macpherson's first rendition of Senate Bill 100, introduced in Fall 1972, called for the creation of fourteen boards that would create plans for their respective regions of Oregon, under the supervision of several layers of bureaucracy: a new state-level Department of Land Conservation and Development, a commission made of citizens appointed by the Governor, and an oversight group in the state House and Senate. If the entire process failed, the Governor could impose plans or revise inadequate ones. Not surprisingly, Little argued, many Oregonians chafed at the prospect of so much bulky new government, particularly the new fourteen districts the law would have carved in the state. Macpherson and his colleagues had hoped to craft a bill that everyone could support, but "it managed to gore nearly everybody's ox."

The legislators went back to the drawing board and came up with SB 100 as it is known today. The new version retained little but the DLCD. Local counties would draw up their own plans in accordance with goals established by DLCD's policymaking committee, the Land Conservation and Development Commission, which would approve or reject the local plans based on these goals. Little emphasized that the new bill included a crucial new provision the original lacked: a requirement that local governments invent some means through which citizens could participate in the process of formulating plans. In this spirit, the first of the nineteen goals LCDC called for "Citizen Involvement." Mitch Rohse, in his glossary of Oregon planning jargon, provided the full text of these goals, the remainder of which dealt with:

2) Land Use Planning

3) Agricultural Lands

4) Forest Lands

5) Open Spaces, Scenic and Historic Areas, and Natural Resources

6) Air, Water, and Land Resources Quality

7) Areas Subject to Natural Disasters and Hazards

8) Recreational Needs

9) Economy of the State

10) Housing

11) Public Facilities and Services

12) Transportation

13) Energy Conservation

14) Urbanization

15) Willamette River Greenway

16) Estuarine Resources

17) Coastal Shorelands

18) Beaches and Dunes

19) Ocean Resources

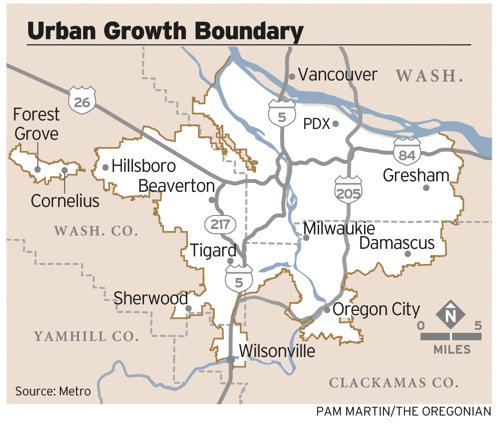

The labels themselves sound extremely general, but buried in the goals are some consequential details. The "Urbanization" standard, for instance, stipulated that "urban growth boundaries shall be established to identify and separate urbanizable land from rural land." The UGB requirement directly addressed the issue of sprawl that first set Hector Macpherson on his quest, while drawing more intense political struggle than any other aspect of the program. Local governments were charged to draw lines that would allow for twenty years of growth; this requirement was sufficiently elastic and subjective that it invited a good deal of haggling between state and local governments, as well as among landowners whose agendas varied.

Scholars have situated these political developments in a larger pattern called the "quiet revolution." Fred Bosslman and David Callies invented the planning usage of this term in their 1972 study The Quiet Revolution in Land Use Control, which touched on Oregon's early efforts at state involvement in managing land and growth. Looking back from the early 1990s, Gerrit Knaap and Bill Nelson argued that Oregon was on the frontlines of a movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s to take a large portion of control over land away from local governments. They classified Oregon as a "first-generation planning state," along with Hawaii, Florida, California and other states that took different steps toward comprehensive planning during this period. Georgia, Maine, New Jersey, Washington, Rhode Island, and Connecticut began to develop similar laws in a later wave of statewide planning, but somehow Oregon has emerged from both generations as the state perhaps most closely associated with enlightened planning. "Oregon has nurtured and enhanced its land use program" for several decades, Knaap and Nelson wrote, serving as a model when the second group of states began to formulate their own new laws.

Calling it a quiet evolution rather than revolution, Michael K. Heiman argued that the new involvement of states like Oregon in land-use planning was just a further step in the long process of organizing land for capitalist production. Middle and upper class liberals had initiated city planning and zoning in the early twentieth century to serve their own interests, developing property for the ends of the biggest and most influential landowners. "Since the mid-1960s, however, a majority of the states have reassumed a share of the police power originally delegated to municipalities sufficient to address land use issues deemed to be of more than local concern," Heiman said. In his view, the reformers of the 1920s were not that different from later liberals like Tom McCall, although some of the buzzwords, like environmentalism, happened to be new. In Heiman's view, capitalism was the only relevant philosophy in city planning.

Although The Quiet Evolution dealt with the development of planning in New York's Hudson Valley, much of its analysis fits with analogous events in Oregon. Limiting urban growth meant setting a boundary twenty years or more out from the then-current built environment, which suggests that the program's aim was not to curtail development but promote a particular vision of development. This vision, as Heiman suggested, would benefit some and not others. Research by Gerrit Knaap and Bill Nelson has shown that urban growth boundaries redistribute wealth from areas outside the line to those inside, since property values increased for urbanizable land. The authors pointed to the example of Salem, where some landowners fought to have their holdings included in the boundary in order to reap any windfall that might follow from the categorization. More importantly, Knaap demonstrated that UGBs could function as "timing constraints," sending signals to owners, investors and developers about when land would be used. The regulation fostered economic efficiency by introducing an element of predictability into property development. Farmers could run their operations safe in the knowledge that, for the foreseeable future, their land would be slotted for rural usage, immune to the threat of speculative pressures that might force them to quit farming and sell out. Meanwhile, developers and homebuilders could know which land to buy and how soon to do it, while benefiting from the increase of land values along the inner rim of the UGB.

Matthew I. Slavin's work on economic development policy in Oregon corroborates Heiman's view of planning as a means of enhancing the real estate market. A too-free market could make doing business difficult, as had occurred during Oregon's frenetic growth of the 1960s and 1970s. According to Slavin, "The period leading up to 1973 often saw urban sprawl disjoin the type of land holdings best suited for large-scale industrial and commercial development in Oregon." Major business enterprises found that the only suitable lots of land were far removed from essential services, while random development had produced many small parcels within reach of the urban infrastructure. As a result, said Slavin, the Association of Oregon Industries lobbied hard for the land-use planning legislation and tried to influence its content as much as possible.

Slavin's portrayal of the lobbying and legislating process matches up with the Heiman perspective. Groups like the AOI pursued state-level legislation because local authorities were not managing property with sufficient competence and expediency. "[Planning's] strongest advocates have included representatives from prodevelopment and large-scale enterprises," Heiman said. "Periodically these businesses were concerned that local municipalities were ill prepared or unwilling to accommodate and service their needs." Large, well-organized developers had the greatest stake in a more orderly business environment, and they seized the tools of government to produce a real estate situation more conducive to their interests.

Numerous scholars have conceded that planning served to reorganize the land market along more efficient lines, but few shared Michael Heiman's critical perspective of this process. Carl Abbott, for instance, appeared to come to much the same conclusion as Heiman: "It is particularly relevant to note that the basic function of modern land use planning -- to assure predictability in the process of land conversion and development -- coincides with an essential characteristic of public bureaucracy." However, Abbott valued the better procedures of bureaucracy, viewing them as essential to pursuing the public good through participatory politics. Heiman perhaps rightly complained about the orientation of most scholarship on planning. "Conventional treatments of the so-called quiet revolution are ideological, indeed participatory advocacy for the most part," he observed. Certainly, scholars like Knaap, Nelson, Abbott, and others who have written on Oregon planning share a liberal, progressive ideology that assumes the essential potential of state action for the common good. These authors regularly acknowledge the pluses and minuses that accrue to different interest groups in the workings of public policy, but they do not believe that the state is necessarily a tool of a capitalist class.

Nevertheless, capitalists of various sorts are hard to avoid in this body of literature, as developers and homebuilders have been crucial and influential constituents of the planning regime. No observer has suggested that business has been solidly antagonistic to the planning program, but scholars have disagreed about how and when business interests supported statewide planning. Some have argued that private sector leaders had been in the forefront of land-use policy from the start, and the economic analyses of Knaap and Nelson suggest that developers, farmers and others would have found much to like in the urban growth boundary system. Charles E. Little's account of the creation of SB 100 reveals the deep involvement of business leaders in the legislative process. Senator Hector Macpherson's Land Use Policy Action Group, which first laid out the ideas and proposals that became the LCDC system, included, "local government planners, economists, specialists in agriculture, businessmen, and environmentalists." Even in the law's ill-fated first rendition, Little observed, "the powerful economic interests of the state -- developers, industry, loggers, farmers, tourism groups -- had not, in any organized way, come out flat-footedly against the bill as a whole." When Macpherson and his allies sought to rework the bill to make it passable, they put together a committee that included representatives from manufacturing, homebuilding, lumber and other industries. In this play-by-play description of the law's genesis, Little never let business leaders slip out of view for long. The bill that resulted, it seems, must have been palatable to a variety of industrial interests.

However, a narrative also exists in which business leaders dallied with opposition to land-use planning before eventually coming around in the program's second decade. H. Jeffrey Leonard has argued that business support was unreliable during the various referenda of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The economic downturn of this period had been particularly harsh for Oregon, and many citizens were beginning to question whether land-use planning had made the burden of depression heavier for their state than others. According to Leonard, the liberal, environmentalist group 1000 Friends of Oregon realized what might be lost if planning could not be reconciled, in the public mind and policy, with economic development and decided to take action. "In working to prod local governments to comply with LCDC's housing and urban development goals," Leonard wrote, "1,000 Friends played a pivotal role in converting the homebuilding industry from opposing the state land-use program in the statewide referendum in 1976 to supporting the program in a similar 1978 referendum."

Gerrit Knaap and Arthur C. Nelson have explained the shift of business attitudes toward planning by emphasizing the difference between the formulation and implementation stages of city plans. The first phase of the program required local communities to draw up plans with urban growth boundaries and other features consonant with the LCDC's nineteen goals. The state would then review these plans to determine if local planners had strayed from its ideals on Housing, Transportation and other aspects of growth. LCDC rejected some plans and caused immense frustration in many communities, while localities dragged their feet so much that all plans were not complete until 1986. However, as Knaap and Nelson observed, the balance of power shifted considerably once communities began implementing plans. The "burden of proof" now rested on the state government to challenge local decisionmaking, whereas before city planners had to be able to justify their plans to LCDC. The dynamic between interest groups changed even more dramatically. "Local land-use control favors local developers and local landowners and frustrates environmentalists, such as 1000 Friends," Knaap and Nelson said. Environmentalists and service industries had been successful in influencing the state level of planning, which mostly involved formulating plans, and resource-based industries and local groups had been more effective in the implementation stage. Although Knaap and Nelson insisted that the program was not wholly owned by developers, the authors did concede that this interest group had enjoyed unique success throughout the planning process. "Developers," they said, "appear remarkably effective at both levels of government."

Like economic development, housing has emerged as a pivotal concern of activists, interest groups and, subsequently, the planning regime itself. Any state venture into the development of land will likely influence the nature of human shelter, and housing issues have been present in, if not central to, Oregon's land-use politics from the start. Whether favorable to state housing policies or not, most scholars have acknowledged the ambivalence housing advocates have felt toward the program. As Nohad Toulan observed, the 1973 legislation might have enthused environmentalists and worried business leaders, but antipoverty activists remained undecided about its consequences. Some worried that bounding the cities and limiting the amount of developable land would push up housing prices, with builders gravitating toward the upper end of the housing market. Such consequences might not be foremost in the minds of middle-class environmentalists and other SB 100 supporters.

Other housing advocates saw a more hopeful picture. After all, the statewide goals made "Housing" a priority, with government responsible for providing an adequate range of housing options to citizens. In this spirit, Toulan conceived of Oregon's program as a step forward into a more comprehensive concern with social welfare. The nineteen goals engaged the state on a broad array of issues (housing, transportation, recreation), while making crucial connections between suburban sprawl, low-income housing problems and environmental degradation. Michael Heiman might consider these developments to be merely the extension of state power in the service of capital, but Toulan, like virtually all other students of Oregon planning, interpreted such moves as the ameliorative work of the liberal state.

Where observers do disagree is whether these efforts have achieved their stated aims of improving the quality and diversity of housing. The Metropolitan Housing Rule of 1981, for instance, has been a key point of contention between scholars. This law applied to the areas of Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington counties that make up the greater Portland area. "Jurisdictions other than small developed cities must designate sufficient buildable land to provide the opportunity for at least 50 percent of new residential units to be attached single-family housing or multiple family housing," read the Rule's opening paragraph. The six largest cities within the Metro UGB had to plan for densities of ten or more dwelling units per acre, and most remaining areas were required to plan for eight dwellings or, in a few cases, six dwellings per acre. The Rule allowed for further exceptions in unusual cases, but its orientation was clearly away from the production of free-standing, single-family homes.

Legislation of this kind could clearly help fulfill the mandate of the state's land-use planning goals. If, as Tom McCall so passionately insisted, planning should be used to limit sprawl, devices like the Metropolitan Housing Rule could serve to counteract the excesses of other parts of the program -- such as UGBs drawn so liberally that they extend even farther than the loose twenty-year expectation written into the law. Nohad Toulan has argued that the MHR complemented the statewide program by assuring that planning does not simply produce a curtailed kind of sprawl but, rather, creates desirable content within the limits of city boundaries. "It can be argued that MHR, which came eight years after adoption of SB 100, integrated housing with all its social concerns into the mainstream of the Oregon land use planning process," he said. In other words, MHR gave some socially conscious teeth to the abstract good intentions of the state's planning goals.

Be that as it may, Gerrit Knaap and Arthur C. Nelson have cast considerable doubt on the Metropolitan Housing Rule's ability to influence the actual content of development. They argued that the Rule did not go far enough in dictating the form of new housing, encouraging rather stipulating high-density growth. "Although the Metropolitan Housing Rule made multiple-familyÖ housing possible, it did not make it profitable," Knaap and Nelson said. "In the absence of constraints on urban land supplies, the land price remained low; and low land price creates incentives to use more land in development." Several aspects of the planning program in general and MHR in particular conflict with their argument. Setting urban growth boundaries did make the included land more valuable, thus putting some pressure on developers to use space more carefully. Moreover, the MHR did more than encourage or allow higher-density development. The Rule actually set out specific requirements for the proportion of new growth that would house multiple families and the number of units that must, on average, occupy a single acre.

Evidence suggests that the problem may not be in the Rule itself but in its enforcement. Knaap and Nelson noted that new growth under the MHR found 9.58 units per acre in areas with a ten-unit requirement, 8.42 in eight-unit zones, and 3.09 in six-unit neighborhoods. One could construe these figures as evidence of the law's failure or success, but they certainly imply that, in at least some areas, compliance and enforcement have been less than complete. Elsewhere, the authors' data send similarly mixed signals. "The percentage of multiple-family starts in the Portland area did increase markedly after 1984," they wrote, "but the share of multiple-family housing starts was also high in Portland during the early 1970s, long before the Metropolitan Housing Rule was adopted." Here again Knaap and Nelson based their argument against the effectiveness of the program on inconclusive evidence. Whether housing density rates had been high over ten years earlier does not bear on whether the MHR successfully implemented its own requirements in the mid-1980s.

Knaap and Nelson went on to use an argument that pops up frequently in assessments of Oregon policy: that the tangible results of land-use planning turned out to be little different from parallel developments in other states. They extended their critique of the Metropolitan Housing Rule by observing, "What is more, the pattern of multiple-family starts in Portland is not discernibly different from the pattern in other western cities." Nohad Toulan made a similar claim, but with a rather different bent. It may be true, he admitted, that developers did not completely comply with the density requirements. Whether housing affordability and urban congestion have increased or decreased remained an open question. "There is no evidence that, with growth management and strict housing rules, the Portland area is in any worse position than similar areas in other parts of the country," Toulan insisted. Since growth management carried with it other, less tangible benefits, "this by itself is an adequate measure of successÖ" If the program managed to accomplish some positive ends without causing discernible damage, then it had worked well. No news is good news. For Knaap and Nelson, Portland's similarity to other cities was a sign of the shortcomings of land-use planning, while for Toulan the comparison could be as a success story. Scholars often point to such comparisons to support their interpretations of Oregon planning, whether to counter claims that planning has done damage (like Toulan) or to show that the program has been ineffectual.

The question might be better put if scholars compared not Oregon to other states but, rather, Portland to other cities. No writer has yet alleged that Goal 14 has produced enlightened housing results anywhere else in the state. As Nohad Toulan observed, "The approach has been generally successful when regulations and guidelines went all the way in defining the expected outcome," but greater Portland was the only region that has taken independent action to turn the statewide housing goal into a more precise, specific instrument. The LCDC has required all localities to draw up plans that conform, in some way or another, to the nineteen planning standards, but the agency has probably been reluctant to impose stricter regulations like the Metropolitan Housing Rule on communities. One could argue that a success story in Portland is not insignificant. H. Jeffrey Leonard estimated that 80% of the state's population lives in the Willamette Valley, and Portland has long surpassed all other Oregon cities in size. Portland, then, is much of Oregon in numerical terms, but it is still just Portland.

Whether they believe that the planning regime has really delivered the goods or not, most scholars agree that the program has adroitly responded to issues like housing and economic development over the years, and one might reasonably ask why the LCDC system has managed to survive serious doubts on these fronts. The severe economic downturn of the early 1980s, for instance, led many to question whether urban growth boundaries and other regulations had choked off Oregon's growth possibilities, setting the "conservation" in LCDC too high above "development." Similarly, the Metropolitan Housing Rule can be seen as a response to concerns that planning had done too little to determine the type and variety of housing on the market. Scholars have trotted out a variety of explanations for the continued success -- or, at least, existence -- of statewide planning and the UGB system in Oregon. The broad coalition of interest groups that supports land-use planning is, perhaps, the most ubiquitous character in all these studies, more so than environmentalists, neighborhood associations or any other player alone. The question, then, is why and how the coalition that spawned SB 100 in 1973 and carried it through four ballot box battles managed to stick together for so long.

Several observers have argued that Oregon's homogeneity made the cooperation between interest groups possible. Developers, farmers, urban professionals and others could find common ground behind the land-use planning program because they already had so much in common. As Carl Abbott noted, many Oregonians can trace their lineage back to Anglo-Saxon northeasterners who first settled the state in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The preponderance of Episcopalians and Congregationalists over Baptists and Roman Catholics in the state suggests such shared origins. H. Jeffrey Leonard cited the words of land-use attorney Ed Sullivan to explain the success of planning in Oregon. "The absence of cohesive minorities in Oregon may be a bigger factor in maintaining consensus and avoiding irreconcilable conflict than people think," Sullivan said. "For the most part, Oregon is dominated by an extremely homogeneous, white, middle-class population." The homogeneity argument alone is unsatisfactory. Somewhere in the background lurks a racist and unfounded assumption that white, black and brown people could not agree on public policy as have the solid Anglo-Saxons of Connecticut derivation.

Carl Abbott has gone farther than most in expanding the simple observation of social similarity in Oregon to a broader question of political culture. His essay "The Oregon Planning Style" traces different strands of moralism and conservatism in the state's history and politics, arguing that Oregonians have traditionally valued the public interest over the individual. The official state heroes, after all, are iconoclastic crusaders for the common good like the progressive William U'ren and the feminist Abigail Scott Dunaway. Abbott also pointed out, though, that the people of Oregon have been conservative in matters of taxation and state intervention, pursuing the public interest at least partly by carefully guarding the status quo's best elements. The state's trademark environmentalism, he suggested, was the perfect example of a progressive politics that sought to preserve the past. "In a conservative and moralistic state, land use planning has allowed Oregonians to be community minded and "good without being revolutionary," he observed. To Abbott, the participatory, procedural innovations of land-use planning were also distinctly Oregonian. "It is not just the content of the statewide goals that is rooted in Oregon's political culture," he argued. "The goal-setting process used in Oregon planning draws directly on the state's core values. It has tended to be participatory and explicitly rational."

H. Jeffrey Leonard complicated this view of Oregonian political culture by highlighting the social and political outlook of the state's newcomers, many of whom came from California. In his study for the Conservation Foundation, Leonard suggested that it was not Oregonians who pushed for land-use planning so much as the outsiders, most of whom naturally gravitated to the economically vibrant Willamette Valley. "Nearly 40 percent of all immigrants to Oregon had come from California, where many had witnessed the decline of agriculture and loss of prime farmlands in California's coastal valleys," he wrote. "These residents provided the core of a constituency committed to protecting agricultural land from the encroachments of urban development." Few California emigres were likely to move into the sagebrush and timber country of Oregon's vast interior, where growth in both population and economy was low, and support for land-use planning was certainly strongest in the Willamette Valley, among farmers and urbanites alike.

If Leonard were right about the influence of the new Oregonians, then Tom McCall's rhetoric of exclusion begins to sound more like bluster than bravery. When he implored outsiders to "visit, but please don't stay," the governor may have been wagging his finger at his own real and potential supporters. Indeed, references to the ravages of California abound in nearly every account of the planning program's birth. In his early assessment, Charles Little quoted an Oregonian woman, Sherry Smith, saying, "Mention the Santa Clara Valley around hereÖ and everybody turns green." Considering the influence of in-migration during the robust years of the sixties and seventies leads one to a rather different conclusion than McCall and company had assumed. The endless jeremiads against Los Angeles in the literature of Oregon planning might have derived from bitter experience as much as the neighborly anxiety of native Oregonians peering over the border.

Of course, Californians spooked by San Fernando sprawl could not have remade Oregon politics from scratch. They moved into a state with its own institutions, which bore the marks of the outlook of past and present citizens. Judging from the available research, a synthesis of Carl Abbott and H. Jeffrey Leonard's arguments looks most reliable. The dramatic emergence of environmentalist legislation and statewide planning in the sixties and seventies probably resulted from the convergence of traditional Oregonian ideals and the political experience of Californian migrants in the Willamette Valley during this period.

Talk of natives and immigrants aside, Carl Abbott's work continues to interest because of his emphasis on bureaucracy and the culture that supports it. The word "bureaucracy" has taken on such negative connotations in the contemporary United States that Abbott seems somehow amiss in focusing on its benefits. Words like "process," "procedure," or "structure" might serve better to explain the political mechanisms that Abbott believed made the land-use program both responsive and resilient. From the beginning, state planners spent resources on efforts like the "rolling public involvement shows" of 1974, which elicited the concerns and opinions of ordinary citizens about their physical environment. Abbott argued that these aspects of the program did more than provide input from regular Oregonians; it also integrated thousands of participants into a base of support by making them feel they had a stake in the process.

The history of neighborhood groups in Oregon planning provides further examples of the state's cultural habit of including and incorporating. Several scholars have pointed out the often oppositional role these organizations could play in planning, particularly when the arena for dispute moved to the city or county level. Nohad Toulan, for instance, said that such groups often disliked new zoning rules for fear of losing "community character" to high density development. However, Carl Abbott demonstrated how Portland responded to the increasingly militant stand that many neighborhood organizations were taking against city planning in the early 1970s: activist Mayor Neil Goldschmidt established an Office of Neighborhood Associations that would provide these groups with a direct avenue of communication to local government. The ONA "furnished a set of ëadvocate bureaucrats' whose first concern was to articulate neighborhood interests," Abbott said. "The procedures of physical planning were viewed from the bottom up as tools for achieving the social and political goals of stable population and local control." These bureaucratic innovations took shape primarily in 1974 and 1975, just as statewide land-use planning rolled into motion. Institutions like the ONA probably helped ease conflicts that would later result from state and local planning decisions, from urban growth boundaries to the Metropolitan Housing Rule. Whereas local groups could have remained in perpetual conflict with the larger planning agenda, the Portland city government sought to neutralize discord by distributing "stakes" as far and wide as possible.

How far and how wide has that spreading process gone, however? Oregon planners and leaders have sought to craft as broad a coalition as possible, but scholarship suggests that some groups and individuals have remained permanently on the outs. Those people, for instance, who ideologically oppose state regulation of land have found little comfort over the years. Scholars suggest that the consensus on the need for planning has been frustratingly strong. "Even the opponents of the LCDC system, in other words, argued about how to plan, not whether to plan, leaving the goals themselves above the political battle as examples of right thinking," Carl Abbott observed. A flip through recent pages of the Portland Business Journal affirms that even the business community seldom questions land-use planning itself, but instead debates the finer points of planning decisions. Abbott noted that Oregon lacked the sort of "Sagebrush Rebellion" that gripped neighboring states like Nevada and Utah in the 1980s, in which discontented citizens organized behind a "radical individualist agenda" and the idea of property rights. Of course, the antiplanning referenda of the late 1970s and early 1980s could be construed as Oregon's nearest equivalent of such an insurgency. Perhaps the property activists resigned in frustration after four failed attempts to stop the state's depredations on their frontyards.

Research has also occasionally provided the example of a group that refused to "play ball" when the state entreats it, ONA-like, to join the process. Carl Abbott discussed a conflict that emerged in the 1980s when businesses and the city government sought to redevelop Portland's North End, where many homeless people lived in a "skid road." The plan was first hatched in the city's Downtown Plan of 1972, but the surge in homelessness during the time of Ronald Reagan put greater pressure on the neighborhood. Social service agencies objected that the new commercial ventures would threaten their ability to care for these unfortunate citizens. "The Portland solution to this classic land use conflict was to bypass political debate with organizational negotiation," Abbott wrote, as the two sides made a truce: service groups agreed to limit the number of shelter beds in the area and the Development Commission pledged to push for more affordable housing. Whether such promises could do much good for troubled individuals with little access to money is quite unclear. In any case, one consequence of the new coalition was unmistakable. According to Abbott, a "maverick agency was frozen out of the district by political muscle and bankrupted by the evaporation of contribution. No organized outsiders remain to threaten the social service/low-income housing coalition."

This sense of political mechanism helps soften an image of Oregon planning that portrays the entire regime as, firstly and persistently, the handmaiden of developers and other business interests. One could read the histories of Charles Little, Matthew Slavin, Gerrit Knaap and others as a story in which business had the first and last word on everything. As Little showed, private sector representatives helped craft the land-use planning bill in the state legislature, and, as H. Jeffrey Leonard suggested, key industries still demanded considerable wooing if they were going to stay in the support column when LCDC encountered electoral challenges. If nothing else, one could suggest that business set the terms of debate and possibility in which Oregonians hammered the program out.

While the influence of developers and other industries has been undeniable, the literature suggests that the inclusive political character of Oregon planning has at least checked business interests with a steady flow of claims from environmentalists, neighborhood groups, and housing advocates. Indeed, 1000 Friends of Oregon has emerged in nearly all studies as the heaviest of political heavyweights in land-use politics. Gerrit Knaap and Bill Nelson probably correctly observed that environmentalists enjoyed less influence at the local level than on higher planes, but numerous scholars have recognized the power of 1000 Friends to influence policymaking and enforcement through activist litigation. The organizational baby of Tom McCall came to agitate on issues ranging from housing to transportation, overcoming the caricature of a narrowly ecological group. Moreover, Deborah Howe argued that determining the parameters of discourse is not the province of developers alone, if at all. "1000 Friends is the primary generator of information about the Oregon planning program," Howe wrote, "and therefore the informaton they provide tends to become the common wisdom." Apart from the occasional academic investigator, 1000 Friends appears to have exercised a near monopoly on producing research about Oregon planning, generally titled toward their own policy positions.

The inclusive quality of Oregon planning, and its attendant durability, may be traced to the original structure of the legislation itself. Consider two observations about the land-use system together: Charles Little described the bill as an "empty vessel" by the time it escaped gutting and reshaping in committee, and Nohad Toulan implied that SB 100 opened new vistas for the state's social engagement. The system's attention to such a wide range of social and political issues -- nineteen of them, in fact -- has provided an opening for later groups to enter the scene and legitimately register their claims by filling in the empty spaces. "The high number of goals may also explain why some goals have become high-threshold concerns, receiving a great deal of attention, and others, such as the Energy Conservation Goal (Goal 13) and Historic Preservation goal (Goal 5), have been relegated to the back burner." As Abbott suggested, Oregon's political culture led its leaders and citizens to craft an involving, engaging process for planning, and this system seems to have offered enough stakes to enough people to preserve itself in fat times and lean.

Pleasing everybody, however, might eventually mean pleasing no one. All the concessions it took to make a consensus this long-lasting could add up over time. The boom times of the 1990s were particularly kind to Portland, but such bountiful growth may have put a pressure on the housing market unknown in the prosperous 1970s, when there was plenty of land left within the boundary, or in the 1980s, when severe depression meant that little new housing was built or sought. Some environmentalists and planners have been dissatisfied with the ability of UGBs and density requirements to constrain suburban sprawl over time. Most notably, the designer Andres Duany sought to "punch holes" in the Portland myth after taking an unguided tour to the outer reaches of the metro area. "To my surprise, as soon as I left the prewar urbanism (to which my previous visits had been confined)," Duany wrote, "I found all the new areas on the way to the urban boundary were chock full of the usual sprawl one finds in any U.S. city." Duany argued that environmentalists had been hoodwinked by hard-driving developers who got whatever they wanted while no one was looking. "There is still the sort of developer who should be interviewed for the Smithsonian oral history archives along with sharecroppers and buffalo hunters," Duany wrote. "They survived only because their natural predator, the environmentalist, has been neutralized by the sense of security the urban boundary provides."

Duany's invective recalled the insinuation -- albeit more open and aghast here than elsewhere -- that land-use planning has been the tool of developers all along. For all the guesses of later scholars, a better answer to the development question could be found in Charles Little's first foray. It is tempting to think that a program of boundaries would be about limits alone. Certainly, the heated rhetoric of the program's early 1970s origins carried antigrowth connotations, as farmers fretted about runaway suburbs and "Not Los Angeles" was a rallying cry. Anyone sitting in the Oregon legislature when Governor Tom McCall railed against "condomania" and "the grasping wastrels of the land" might have thought that Oregonians wanted to put the kibosh on growth altogether. Indeed, scholars have found the McCall tirade so irresistible that almost every book on Oregon planning quotes him at length, providing readers a window into the language and emotion of the time.

Beneath the flourishes, however, what sounds like "antigrowth" turns out to be something like "smart growth." Little closed The New Oregon Trail by interviewing McCall, and their conversation revealed much about the ideological center of the new land-use planning crusade. "We're not as 'violent' as pure preservationists want us to be," the governor said. "Nor are we as much of a consumer and user of natural resources as perhaps some industrials would want us to be." He told the people of the state that guarding Oregon's resources then would pay off later, when businesses would line up at the door to make use of its high quality of life. "A little belt-tightening now," he said, "would give us the ability to pick and choose later on." The emphasis was on facilitating future development rather than stopping current development. Just as urban growth boundaries helped to organize the land market for greater efficiency, the planning program sought not just to conserve resources, but to conserve them for later use.

It should be no surprise to Andres Duany that the Portland landscape resembles the rest of the United States more than its city-on-a-hill image admits. Features like urban growth boundaries and minimum-density housing may not be precisely business-as-usual, but they are a matter of business nonetheless. Oregon could not have opted out of the bigger landscape even if it wanted to do so. The state was still enmeshed in the car culture, federal housing policies and other great phenomena of American life, sharing also a set of economic and political actors -- homebuilders, developers, resource industries -- who assured that the state would not wish to opt out in any case. The planning legislation of 1974 created a Land Conservation and Development Commission, and no word of that title should be forgotten. They were probably not haphazardly chosen. The literature on Oregon planning suggests that the state's people have managed to make a still striking difference in how they develop their physical and social surroundings. Suburbs may have been built and some farms may have been paved over, but probably fewer than would have occurred otherwise. Oregonians were able to navigate the dangers of political discourse thanks to flexible legislation that opened up new possibilities for social intervention and a political culture that favored cooperation and participation. Given all the pressures on the American landscape, even making a mixed bag takes a good deal of aplomb.

- Alex Cummings**

Bibliography

- Abbott, Carl, Deborah Howe and Sy Adler. Planning the Oregon Way: A Twenty-Year Evaluation. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 1994.

- Abbott, Carl. Portland: Planning, Politics, and Growth in a Twentieth Century City. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983.

- Bosselman, Fred and David Callies. The Quiet Revolution in Land Use Control. Washington, DC: Council on Environmental Quality, 1972.

- Cogan, Arnold. "Critic of Portland Planning Misses Mark." Oregonian. 2 January 2000.

- Duany, Andres. "Punching Holes in Portland." Oregonian. 9 December 1999.

- Heiman, Michael K. The Quiet Evolution: Power, Planning, and Profits in New York State. New York: Praeger, 1988.

- Knaap, Gerrit and Arthur C. Nelson. The Regulated Landscape: Lessons on State Land Use Planning from Oregon. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 1992.

- Leonard, H. Jeffrey. Managing Oregon's Growth: The Politics of Development Planning. Washington, DC: The Conservation Foundation, 1983.

- Little, Charles E. The New Oregon Trail: An Account of the Development and Passage of State Land-Use Legislation in Oregon. Washington, DC: The Conservation Foundation, 1974.

- Rohse, Mitch. Land-Use Planning in Oregon: A No-Nonsense Handbook in Plain English. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University, 1987.